|

Don't Come Knocking / Battle in Heaven / L'Enfant Wassup Rockers A Scanner Darkly The Night Listener [FILM COLUMNS OF 2005] [FILM COLUMNS OF 2004] [OTHER HELL FILM WRITING...] |

HELL ON THE MOVIES 2006

Richard Hell's movie column for BlackBook magazine, which appeared 2004-2006

Column #11, Mar 2006

Don't Come Knocking / Battle in Heaven / L'Enfant

Don't Come Knocking director: Wim Wenders; script: Sam Shepard, story by Shepard and Wenders; cinematography: Franz Lustig; cast: Sam Shepard, Jessica Lange, Tim Roth, Gabriel Mann, Sarah Polley, Fairuza Balk, Eva Marie Saint

Battle in Heaven director: Carlos Reygadas; script: Carlos Reygadas; cinematography: Diego Martinez Vignatti; cast: Marcos Hernandez, Anapola Mushkadiz, David Bornstein, Berta Ruiz

L'Enfant (The Child) director: Jean-Pierre Dardenne, Luc Dardenne; script: Jean-Pierre Dardenne, Luc Dardenne; cinematography: Alain Marcoen; cast: Jérémie Renier, Déborah François, Jérémie Segard, Fabrizio Rongione, Olivier Gourmet

As a rule, I don't write about movies I don't like, just because it seems like a waste of space. I didn't see any I liked for this issue, though, so I'm finally writing some straight pans. There were three movies that turned out to be bad for similar reasons, having to do with how they tarted themselves up in art drag when really all they were was the drag part. One was more or less simply disappointing, one I hated, and one was frustrating in a kind of complicated way. After all that, I'll lighten up with some good news at the end.

The plain disappointment was the new Wim Wenders film, Don't Come Knocking, written by and starring Sam Shepard. Wenders has always been an over-romantic Americanaphile, the kind of European who wants to make western road movies with a lot of motels and desert, fronting an electric guitar soundtrack. At the same time, I respect his casual, eye-oriented style. I've liked some of his documentaries and remember being susceptible to Wings of Desire too, though I haven't seen it for a long time. Paris, Texas, his earlier movie written by Shepard, was too ploddingly portentous for me. Shepard, before he was a movie star, was the playwright hero of the 1970s and has continued to be that for two or three generations of rock & roll cowboys of the theater, reeling off drama into the dawn the way most people go to sleep. He's successfully worked his radiotronic rabbit tooth or his silver dog smell or whatever it is on me more than once over the years. I liked a lot of those plays, and I also respect, as I do in Wenders, Shepard's anti-Hollywood priorities. But this movie is so bad and bad in such a way as to make me wonder if I could have been wrong about the earlier Shepard. This shit is too fucking macho, faux-mysterioso, and too much a mental mess, like a blind cut-up of Sam's and Wim's own faded old material. It's strange to see these guys, who so conspicuously reject Hollywood formulas, making works as limited to formula as the stuff they oppose. There are a whole lot of good looking shots in this movie: of western desert, of the big-skied beat-up streets of downtown Butte, Montana, of outrageous disco-squared Nevada casinos, of the star's vintage Packard wheeling down the two-lane, etc. But that shit is as tired by now as teeth-gnashing mega-pixel dinosaurs. More tired. And who cares about another jacked-in cowboy having an existential crisis all over his family? He should do that on his own time. Eva Marie Saint as Shepard's mom is really great though. I wish they'd stayed at her house and let her be the movie.

If Don't Come Knocking is derivative of its own filmmakers, the other two movies here are counterfeits of interesting recent artistic trends. Apparently, there are enough art movies succeeding these days that what at first was fresh gets immediately degraded by imitators. (The one film I've walked out on in these two years of movie reviewing was Napoleon Dynamite, a moronic and mean-spirited psuedo-type of Todd Solondz's great Welcome to the Dollhouse.) The movie I hated is called Battle in Heaven. It's from Mexico and is the second feature by director Carlos Reygadas. The techniques that Reygadas exploits here are those originally used sensitively and organically by directors like Abbas Kiarostami (Iran), Bruno Dumont (France), and their cinematic godfather the incomparable Robert Bresson: employing non-actors in stories about ordinary, usually poor, people in mostly everyday scenes -- though the everyday scenes often include violent death, frequently suicide. Lately, explicit acts of sex have joined the real life detail of some of them, too. Battle in Heaven opens with a shot travelling slowly, from a mushy face, down the full-frontal body of a very fat and homely naked guy who you eventually see (in unforgiving closeup) is getting his purplish penis sucked by a pretty young woman. The imagery -- the camera work, lighting, angles and material subject -- definitely get your attention. You want to trust this director because he's showing you strong stuff. You want to find out where he's going to go with it, what he's going to indicate to you about its importance. Unfortunately, he goes nowhere and means nothing. The movie is pure exploitation masquerading as art. It's degrading to watch. It's all strategic smoke-blowing, the smoke being filmic techniques that we've learned from the director's betters to read as signifying insight and intelligence, but which here are used in the service of emptiness and vanity, emptiness made to further keep your attention with explicit sex and extreme violence. It's pure Hollywood pretending to be its opposite. I'll take Get Rich or Die Tryin' any day.

The frustrating film is L'Enfant (The Child). Isolated from its models and influences, the movie would seem more than worthwhile: it's smart, well-acted, shot well, and compelling. (It actually won the Dardenne brothers, who produced, wrote, and directed it, their second Palme d'Or -- the first was for Rosetta in 1999 -- at Cannes. ) Like Battle in Heaven, it shows underclass folk (and fully credible ones, in contrast to the freaks predicated by Reygadas), carrying out their daily routine. The story is of a dim and luckless 23-year old petty thief and beggar, his 18-year-old girlfriend, and their new baby, on the streets of an industrial city of Belgium. In L'Enfant the roles are played by actors, though they're good enough and the film is shot in such a way -- hand-held camera, natural light -- as to make it feel uncannily real. As in Bresson, there is no soundtrack music. By the time it's over, you're moved, though for me it was against my will, because it all wasn't enough. We've seen it before, in Italian neo-realism, in Bresson.... The climactic scene, which defines the film, is a shameless appropriation from Bresson's Pickpocket. I don't know, this sort of thing isn't unprecedented. Brian DePalma made a lot of enjoyable movies that were homages derived from Hitchcock. But DePalma's movies were intended half as goofy filmfreak larks, not intense depictions of our condition, like the Dardennes' film. There's certainly a lot to be usefully learned from Bresson -- Kiarastami and Dumont prove that -- but this film too narrowly imitates him. It's like if you hadn't heard Little Richard doing "Long Tall Sally," you might think the Beatles' version was great. If you've seen Pickpocket, L'Enfant is kid stuff.

For an up note, I'll point out that DVDs have recently been released of two really good films that you might have missed in theaters in 2005: Miranda July's Me and You and Everyone We Know, and Arnaud Desplechin's Kings and Queen. Both are strikingly original (!), intelligent, and entertaining, the former a whimsical/spooky tale of the quest for romance of a video/performance artist in nowheresville Southern California; and the latter a novelistically complex look at crises in the life of a thirty-five year old French woman (played by the tremendous Emmanuelle Devos). While being very different from each other, they also have a kind of poetic imagination in common, which, in mixing the real with the hallucinatory, makes everything more real (and funny). There's not space to say more, but I think you wouldn't regret renting either. Column #12, May 2006

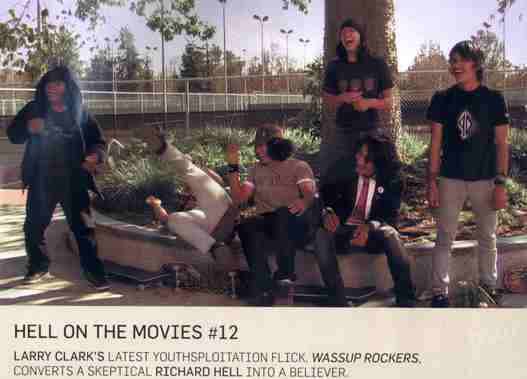

Wassup Rockers

director: Larry Clark; script: Larry Clark, story by Clark and Matthew Frost; cinematography: Steve Gainer; cast: Jonathan Velasquez, Francisco Pedrasa, Milton Velasquez, Yunior Usualdo Panameno, Eddie Velasquez, Luis Rojas-Salgado, Carlos Velasco, Iris Zelaya, Ashley Maldonado, Laura Cellner, Jessica Steinbaum

I hated Larry Clark's first movie, Kids (1995). It was a long voyeuristic leer pretending to be a socially concerned AIDS exposé. It was fucked up to see a teenage girl's HIV used as the excuse to show endless soft-core kiddie porn. The director was fifty when he did that.

Clark had made his reputation as a still photographer decades before, with the books Tulsa (1971) and Teenage Lust (1983). Tulsa showed his gun-playing, drug-shooting, teenage boyhood crowd in Oklahoma; Teenage Lust, fifteen-year-old runaways/prostitutes and their hi-jinks in New York. Both books were packed with youthful hardons, bedraggled pussy, blood-wet drug needles, and other unsupervised poor-peoples' scenarios of pleasure and destruction, all in battered black and white. Most of the kids looked like they were having a fairly good time. The books exposed a typical American way of life that had never been presented to the public so fully and explicitly before. They were great pictures.

There are a lot of missing years in Clark's artistic bio between Tulsa and Kids. He spent some of them in penitentiary and most of them on drugs. Up until he turned fifty, his output amounted to one thin collection of photos every ten years. But those first two books were brilliant. In contrast, his films have been frequent -- five made before this new one in only ten years -- but seriously defective. The actors in Kids were unknown New York skateboarders and club kids, and at least it had the virtue of realistic characters, even if most of them were creepy. Its follow up, Another Day in Paradise, used a weasely James Woods and a grotesquely faked-youthful Melanie Griffith, both out of their depths and mis-directed in roles we had already seen played a thousand times anyway: the semi-charismatic outlaw drughead losers of Scorcese, Tarantino, Gus Van Sant, etc. The young actors (Vincent Kartheiser and Natasha Gregson) who played the protégés of Woods and Griffiths were just as painfully unreal as their elders.

In around nine months stretched across 2000-2001, Clark made three more films: Bully, Teenage Caveman, and Ken Park. Each was awful and featured many more skinny teenagers doing sex and crime offensively if unconvincingly.

To give the director his due, the movies have had one consistent strong point: their photography. They're made quasi-documentary style, with a lot of hand-held camera, and are full of spontaneous-seeming cool ideas of what to shoot in a scene and how to frame it. The location settings -- motel rooms and suburbs and highway strips -- are good looking and atmospheric too. (The music has been more than decent as well -- choice pop and "underground" records mostly.)

But, surprise, all that is a prelude to glory.

The new movie, Wassup Rockers, is a gem. It's about a set of young Latin skateboard punks in L.A. The immediate thing that sets it apart from Clark's earlier films is that for the first time the kids are likeable. They're irresistible, and not just for their charisma, their star-quality youth, but for their charm and openness. At the same time they are not any softer or safer -- or less preoccupied with sex -- than everybody in the earlier movies. These kids have actually lived most of what was filmed, in the deep ghetto of South Central L.A. But, despite the pressures of those surroundings, they seem to have kept not just a basic good will but a kind of pacifism. The word they use for their opposition numbers in the world is "haters." You can see why they wear tight pants and tight t-shirts and relate to the Ramones. They're like the young Ramones: street hardened but not looking to fight, and funny in a way that depends on a kind of amazingly-preserved innocence (though it's an innocence that's almost knowing, cultivated, if that can be said), and happy in each other's company. Wassup Rockers is a perfect title, too: these kids are a personification of rock & roll: sexy, tough, open, young, funny, sharp, and real.

Clark didn't just stumble on the movie. Not only does it proceed from his usual preoccupations, but he spent a year hanging out with the cast to gain their confidence and learn about their lives. Maybe this film is so much better than his others because its methods are more in line with what made his early books so good. The people here are ones the director lived among, and most of the movie comes from experiences of theirs, much of the dialogue improvised. He doesn't have to direct them how to behave, but rather to know how to use their natural behavior.

The film begins with a documentary clip of the main character, Jonathan Velasquez, telling anecdotes about his friends directly into the camera. Then the fictional story kicks in, the narrative line coming from two ideas of Clark's. One was his imagining of what it might be like if two rich Beverly Hills airhead sex-dogs, Paris Hilton and Nicole Ritchie types, were to encounter the skaters; the other suggested by the old youth-gang movie The Warriors, a favorite of Clark's, in which a New York gang is forced to travel across the turf-borders of rival gangs on their way home. In Wassup Rockers, the kids have to find their way back to South Central after a Beverly Hills cop-encounter and a skirmish with the rich girls' boyfriends.

The movie is full of new touches for a Clark movie, too. For one thing it will actually make you laugh. Not just because the kids are naturally great, but because the director wrote some types into the Beverly Hills scenes that are as flamboyantly entertaining as the best John Waters characters. For instance, a falling down drunk, if buff, matron in formal gown, gesticulating and smiling and slurring to Kiko, "With a face like that you're gonna get plenty of ass... With an ass like that, you're gonna get face. I mean with a face like that you're gonna get a lotta girls..." "When?" he suggests. There's some weird slapstick that actually works too, and a couple of strange inspired moments, such as when, as the boys are hightailing it off the grounds of mansion #1, one of them scoots back into frame to plant a kiss on a piece of sexy statuary.

The movie is kind of a contemporary combination of Rebel Without a Cause and The Wild One. It made me realize that maybe the most kind, or even fair, way to look at Larry Clark films is as sensationalist youthsploitation in the vein of movies like those from the fifties. They are like modern drive-in flicks (I Was a Teenage Caveman). In that light, they're not so obnoxious, and this new one is positively transcendent. Column #13, July 2006

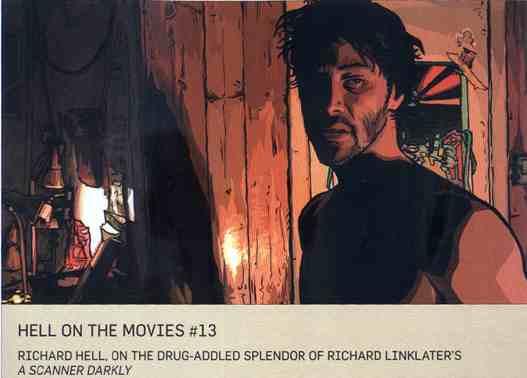

A Scanner Darkly

director: Richard Linklater; script: Richard Linklater, from a novel by Philip K. Dick; cinematography: Shane F. Kelly; cast: Keanu Reeves, Robert Downey, Jr., Woody Harrelson, Rory Cochrane, Winona Ryder

Richard Linklater is one of a set of directors--mostly in their mid-forties--who have in common that they first got national attention fifteen or so years ago with low budget independent features, went on to make standard Hollywood commercial films, but still continue to make other more personal and "experimental" films. I'm thinking of Gus Van Sant (Drugstore Cowboy but also Finding Forrester), Steven Soderbergh (Sex, Lies, and Videotape but also Ocean's Eleven), and Kevin Smith (Clerks but also Jersey Girl), and Linklater (Slacker but also Bad News Bears). Gus Van Sant, who's a little older than the others, is an interesting guy. His shot-for-shot remake of Psycho was ballsy and worthwhile, and so was Elephant, his avante-garde description of the few minutes in the lives of some high school students just preceding a Columbine-type slaughter. Linklater is interesting too, and appealing as a director. Slacker was a really good movie. (Criterion, by the way, has released a fantastic two-disc DVD set around it, with a lot of director commentary, hours of Linklater's pre-Slacker movie-making, and lots of other bonuses.)

Linklater is a wholesome, unpretentious guy who still, after years in cut-throat bigtime kiss-ass filmmaking, maintains his loyalty to a philosophy of individuality, of non-conformity. He likes bohemians and mavericks, people who are thoughtful and questioning and observant, who don't care about conventional worldly success. Those are the kinds of people he makes his movies about. His three best films, Slacker, Waking Life, and this new one, A Scanner Darkly, all flatter with attention the kind of late-night rap-session philosophy and mental riffing most people outgrow by the time they start working for a living. Waking Life was basically about how there's no distinguishing between waking and dreaming. How much slacker can you get than that? It was a lovely movie. (Unfortunately, it seems Linklater has also remained about fifteen where boy-girl romance is concerned. His whole conception of ideal masculinity as evidenced by his use of Ethan Hawke in Before Sunrise / Before Sunset and Matthew McConnaughey in The Newton Boys pretty much ruined those three films...)

A Scanner Darkly was made using the same rotoscoping technique as in Waking Life. The script is played by actors for the camera, but their film images are then reworked by animators using special software that turns the actors into moving paintings. The resulting images are still basically faithful to the subtleties of what the actors did when playing the scenes. It ends up like an animated graphic novel.

The movie is based on a Philip K. Dick science fiction (as were Blade Runner, Total Recall, Minority Report, and Paycheck), which means that it's about the impossibility of separating reality from imagination/delusion/hoax. In this instance, though, the story, more than anything else, is a requiem for Dick's friends--and he, himself--who were killed or permanently damaged by drug use. He was a heavy drug user who wrote his first eighteen books on speed. A Scanner Darkly, published in 1975 and written about seven years before he died of heart failure at age 53, was, according to Dick, the first he wrote without amphetamines. But the story is basically about amphetamines and the accompanying paranoia, primarily Dick's massive fear that nothing is as it seems, nothing can be trusted (including oneself). The movie, which is very closely based on the book, feels not just profoundly sad, but profound, which isn't something you'd expect from either animation or pulp science fiction. (Or paranoid speed freaks for that matter.)

The main actors in it are Keanu Reeves, Robert Downey, Jr., Woody Harrelson, Winona Ryder, and Rory Cochrane. Downy and Harrelson are inspired as crazed speed-freak types. Their paranoid, deluded, megalomaniacal improvisations-become-script are a major contribution to the movie. Cochrane does a completely destroyed nervous-system pretty well too. All the casting seems almost laughably "type," but these actors carry their weight. Even Keanu Reeves's inevitable quasi-Eastwood, but weary, monotonous mutter, works. In fact, my one real reservation regarding the flick is that the performances are so good that I miss seeing them directly filmed rather than processed for animation. I understand though that the rotoscoping made it possible to do the movie for $6- to $8-million, rather than the $20- to $25-million it would have cost to build the sets and do the special effects. So one accepts that; and the animation has its own attractions too.

The story, which is set "seven years from now" (in the book it's 1994), is about a group of grungy brain-damaged drug heads infiltrated by a grungy brain-damaged undercover cop. The sympathies of the text/film are clearly with the addicts, but at the same time it's impossible to tell the addicts from the narcs. In fact, the main character, Arctor (Reeves), is an addict who is also a policeman who reports to his boss on his own activities as well as those of his friends. He informs on himself not only to protect his "identity" from the police--since he and his fellow cops all wear special electronic "scramble suits" that make them unidentifiable multi-person "blurs" when they're not in the company of their drug-user targets--but because he can't really tell who he is anymore. Everyone is equally innocent and guilty, and it's impossible to know with certainty who is who and what they're doing to whom and why. One thing is known beyond a doubt: the drug rules. It's an irresistible powder ("You're either on it or you haven't tried it") that slowly destroys people's brains. It's made from a little blue flower, and is known as "Substance D," or just "death." Life (the drug) is death: the writer nailed it. Probably the only unequivocally repudiated people in the story are "straights"--the ordinary working citizens with small predictable lives. Arctor had once been a straight suburban family man himself, but in a sudden revelation had realized he hated his life and was ready to leave it for "this dark world where he now dwelt [in which] ugly and surprising things and once in a long while a tiny wondrous thing spilled out at him constantly."

This attitude of course--rejection of the straight world--is typical of Linklater's movies. I couldn't help recalling his voiceover commentary to Slacker, which repeatedly names certain (mostly young, and seemingly carefree) cast members as having died in the fifteen years since the movie was made. The Scanner book and the movie made from it end with a dedication to a long list of the author's friends who've been killed or badly impaired in their pursuit of a life devoted to "playing." "They remain in my mind and the enemy will never be forgiven. The 'enemy' was their mistake in playing. Let them all play again, in some other way, and let them all be happy."

It's a kind of "punk" movie really. It's about people who can't accept limits and want life to be more--even if it kills them. They're not really admirable people. The Downey character informs on one friend and casually allows another to die, and somehow there's still something innocent and sympathetic about him. It's all very sad, and interesting, and confusing, and beautiful. Column #14, August/September 2006

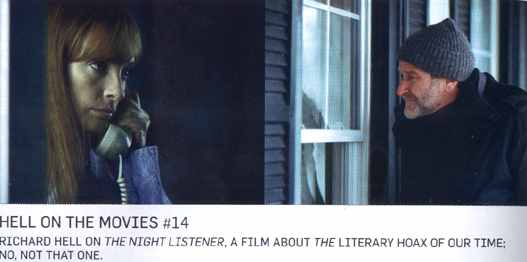

The Night Listener

director: Patrick Stettner; script: Armistead Maupin, Terry Anderson, and Patrick Stettner, from a novel by Armistead Maupin; cinematography: Lisa Rinzler; cast: Robin Williams, Toni Collette, Rory Culkin, Sandra Oh

The Night Listener is the second feature film directed by Patrick Stettner. The first was The Business of Strangers, a sleekly made independent film set in an icy corporate milieu that was raised a few levels by the acting of Stockard Channing and Julia Stiles and Fred Weller. Both that movie and the new one are psychodramas -- about extreme experience leading to self-revelation -- that involve the hoaxing of their main characters by ordinary-seeming psychopaths.

Unfortunately, The Night Listener is pretty well unwatchable. I was compulsively yawning halfway through it. It's based on the novel of the same name by Armistead Maupin, the popular author of the cozy Tales of the City books from which the PBS series was made. I have to say I found the novel, despite billing as a "New York Times bestseller," unreadable too. The subject treated is interesting though. The story is Maupin's mildly fictionalized account of an experience he had a decade ago. In 1993, he was sent the galley proofs of a thirteen-year-old boy's memoir of the horrendous abuse -- and consequent HIV infection -- the kid had suffered at the hands of his parents and their friends. Maupin was moved and impressed by the writing. He not only supplied a blurb for the book but instigated a phone relationship with the author, Anthony Godby Johnson, then fifteen years old, that lasted for six years. He came to regard Tony Johnson as one of his closest friends, practically a family member.

Maybe you can guess what's coming. You're right: the kid didn't exist. He was a hoax perpetrated by a grown woman. Everybody knows who JT LeRoy is, right (or who he used to be)? This isn't him. It's another excitingly sex-traumatized youngster who suckered a lot of celebrities into saying he was a good writer, while actually being a thirty-something woman with some kind of larger agenda. Each of the two con-women successfully built a literary career for her plucky tortured dream-boy by engaging in years and years of celebrity-cultivating phone calls in the guise of the imaginary kid. The celebrities the women tricked talked, in many cases, for hours and hours, month after month, year after year, to the "child." In Johnson's case, as the years passed, she (a woman named Vicki Fraginals), claimed "his" phone voice wasn't maturing because AIDS had prolonged puberty, in Leroy's case, she (Laura Albert) explained that hormone shots meant "he" was no longer "male identified."

Maupin, it must be conceded, leaves room for doubt about whether the boy is faked, trying to make of the story a Vertigo-like mystery about reality, illusion, and imagination in the realm of love. In interviews Maupin specifically names the Hitchcock movie as an inspiration for the novel. (Maupin co-wrote the movie, and it is a straightforward retelling of the book.) Not that he loved the kid as anything other than a son, but he did love him, as he repeatedly emphasizes. And, as he said in an interview about The Night Listener, "Does it matter if we feel something strongly in our heart whether the facts are borne out?" This is the most fun thing about these cases: watching the spin that the hoaxed put on things once the truth comes out. You know it's painful and they're all trying to recover as gracefully as they can manage. But then, if one is really trying to understand the phenomenon, the question becomes, What if it happened to me? Personally, I once played three card monte on the street in New York. I also bought a shrink-wrapped brick on St. Mark's Place for $100 when VCRs were really expensive. Everybody knows cons require larcenous, or at least foolish, victims. But everybody is also susceptible to the right pitch.

Intellectual -- art, literary -- type hoaxes are entertaining, of course, for exposing the falsity of the pretensions of cultural big shots. I can't deny I do have an urge to sneer at the writers and movie stars and journalists who promoted JT LeRoy, at the same time that I also have to admit that I felt kind of left out that "he" never tried to cultivate me too. What do Dennis Cooper and Mary Gaitskill and Marilyn Manson and Winona Ryder have that I don't have? Well, they're more famous for one thing, and by that token, if not others, more chic. Which hurts a little. But I do remember first hearing about Sarah, and being told it was by this kid who'd originally called himself Terminator, who was a cross-dressing former child prostitute at West Virginia truck stops, a teenager when he wrote the novel, and all these famous writers were endorsing it.... I went and bought it that week. It was cute and chirpy about being a twelve-year-old whore at mom's behest; but the writing was affected-sounding and mediocre. Yes, there were arresting hillbilly/lowlife references, but it all just felt like schtick, and I read the buzz as slumming-type gutter glamour, like graffiti in galleries, or chic fundamentalist Christian outsider art, or Norman Mailer promoting literary hard case murder convicts.

Tony Johnson's book, A Rock and a Hard Place, has the same chirpy spirit as Sarah without LeRoy's shred of literary merit, but LeRoy is more interesting as a hoax than as a writer for sure. If somebody could really get to the bottom of the experience of his creator, Laura Albert, the obscure rock musician and fan of Dennis Cooper (another freak for the cultural cutting-edge, but who's an actual genius writer), it would be fascinating. But it'll never happen, any more than, say, anyone will ever be able to do justice to Michael Jackson's trials. If Albert were really savvy she'd give some first-rate writer access to herself and all the data, and share the non-fiction book contract. But judging from the way she's handled things since the story broke -- basically just staying coy and continuing to spin, like Bill Clinton or something -- she isn't savvy enough. But then I suppose probably it's just impossible, anyway, as it is with Jackson: too many reputations are at stake. By all reports "JT"'s celebrity network confided their most intimate secrets to the irresistible, bitchy, super-worldly, little waif. And in Hollywood, they hire pretty hardnosed enforcers. I could definitely see Courtney Love (one of JT's supporters) and Anthony Pellicano (the movie business detective hit man) doing business....

It's the phenomenon of the hoax that's interesting, not the experience of the hoaxed, and that's where the The Night Listener falls short. The question "What is real" is interesting, the answer "Who Armistead Maupin loves" is not. It's also not interesting to watch Robin Williams be sincere. He spends way too much of the movie in miniature Maup-mode, with a little catch in his voice to indicate how emotionally strained out he is. And the corniness is not reduced, as intended, but rather increased, by the way the character cornily acknowledges how corny he is. Maupin wants to appear to make the con the subplot by making a big deal about how vulnerable he (Maupin) is because his long-time boyfriend just left him. As if Maupin is just so full of under-utilized love that it doesn't matter how flimsy is the pretext for its expression. An imaginary abused child will do. Yawn. The greatness of Vertigo was neither the psychology of Stewart's character, nor even the mechanics of the "deception," but the sublime physical correspondence of the imagery to the bottomless mystery of the story it conveyed. Yes it was a story about the shifting and elusive identity of a person's object of love, but it didn't have a moral (like "Does it matter if we feel something strongly in our heart whether the facts are borne out?"). It had no mess and no message. The Night Listener is all mess and message.

On the stands next -- Nothing! No film column from Richard! The new management at Blackbook has fired most of the existing staff, including Richard's editor, and Richard will no longer be writing for Blackbook.